January 22, 2025

Test Driven Development by Example - My thoughts

A book that defines a series of key TDD behaviors and shows them in action!

Test Driven Development by Example has been widely recognised as the origins of the Detroit school of testing which in itself givens the book a bunch of baggage I don't believe it deserves. I do not see this book as the holy bible for classicist test driven development, but instead as a set of verses that exist in the new test-ament of TDD. I chose to read this book due mainly to it's renowned authority in the field of TDD but also at the same time as a mockist tester I wanted to read the book that countered my views on testing. In this review I will take several key learings and with that show you that overall my assumption that I was going to be fighting the ideals brought forward by this book were completely wrong. I will mostly highlight the key tools this book instills and provide my own thoughts on each of them.

Kent Beck the author of this book is well known as the father of extreme programming as well as being one of the original signatories of the Agile Manifesto alongside many other key thought leaders as such as Martin Fowler and Uncle Bob. Over the many years he has continued his efforts to help raise up the entire profession have remained steady and to this day is a key leader and author in our industry. Test Driven Development by Example primarily exists as two e2e examples of how one can apply TDD in their coding flow starting out with a money example and followed through with an implementation of x-unit in python; fully bootstrapped by tests from the ground up. There is a third section with design patterns, however I found that the meat and potatoes of this book was definitely those two sections with the Money example being the most impactful.

Key Lessons

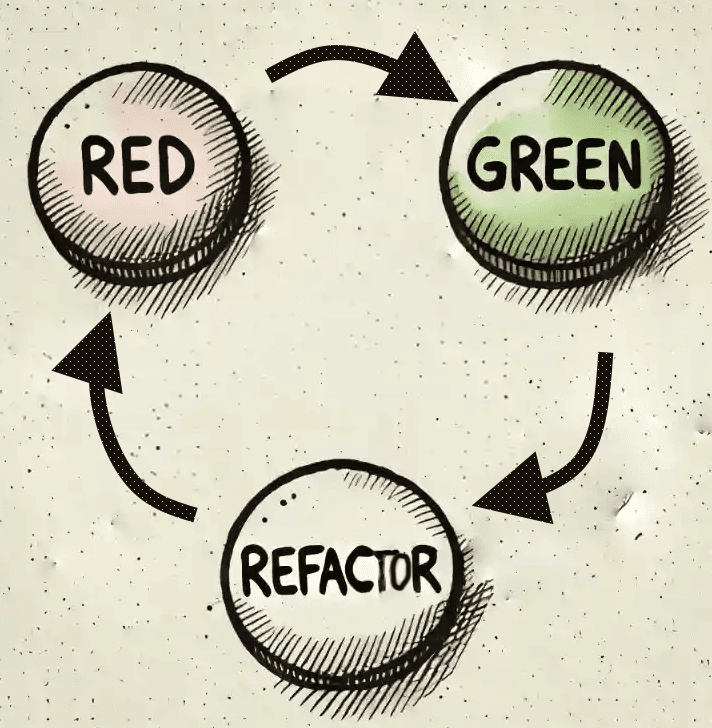

Red Green Refactor

You can summarise most of the book with the following

Red

Write a test that will fail

Green

Make the tests work with the minimum change required, sins permitted!

Refactor

Eliminate the duplication that was required to get the test working

These three steps are some of the most well known and ignored steps to success with TDD or better yet with development in general. Most developers will jump direct to Green and skip out on red but this is shown to be a key mistake! This book has an example of the construction of the Franc money class in which too large of a step was taken, effectively skipping over multiple cycles of Red Green Refactor. To resolve this all that was needed was for the large step to be wound back and smaller cycles taken and the issue is solved.

This shows us that not only do we need to follow red, green refactor we also need to be conscious of how big our green solution is vs the red issue we started with. This is a balancing act that cannot be explained and only really is learnt from experience. Determining how much implementation you should take vs how little is required will take time, experience and tools. Triangulation is one such tool.

Triangulation

Before I can go over triangulation first I need to start out be reaffirming the importance of going from red to green with as little effort as possible. What this means is if your very first test is something like so:

describe('multiply', () => {it.each`a | b | expected1 | 1 | 1`('Should take $a then multiply it by $b to produce $expected', ({a, b, expected}) => {expect(mult(a, b)).toEqual(expected);})})

our implementation should look like:

var mult = (a, b) => 1;

This is very obviously not the correct implementation of multiplication however it allowed us to go from red to green with as little effort as possible. It is at this point that we could take the refactor step to implement the actual mutl function however what if we were unsure of the correct way to write this in a succinct and correct way? We triangulate!

Triangulation is the process of adding more test cases to our suite as to will the correct algorithm into existence. Next

we would add the case {a: 1, b: 2, c: 2}. It is at this point we might find ourselves at the end algorithm, however there

is another way to make both tests pass with the least effort that still isn't the correct implementation:

var mult = (a, b) => b;

This might look like one of the silliest things to have ever written in a code editor ever but this is a key part of tdd. Write as little code as you can to make the test fail (red) then follow that up with the simplest code to make it pass. Once again this can feel absolutely absurd, but what it is doing is forcing us to come to the absolute simplest solution with no more code than the absolute minimum required, which lets us free style with our code and let the groove of our test beats form the eventual final performance.

This eventually leads into the final test in our triangulation exercise of:

var mult = (a, b) => a * b;describe('multiply', () => {it.each`a | b | expected1 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 33 | 4 | 12`('Should take $a then multiply it by $b to produce $expected', ({a, b, expected}) => {expect(mult(a, b)).toEqual(expected);})})

This example is definitely contrived, however what if from the get-go there was a requirement that mult accepted many arguments as we needed a functional way to support multiplying any amount of numbers together. A standard approach without triangulation might look something like so:

var mult = (...args) => args.reduce((accumulator, index, value) => accumulator * value, 1);describe('multiply', () => {it('Should take 1 then multiply it by 2 followed by 3 to produce 6', () => {expect(mult(1, 2, 3)).toEqual(6);})})

Our test passes and we can move along in one fell swoop without three iterations of red, green, refactor... We even got to write our mult function right away rather than the boring test!

However, there is a problem... mult(2, 3, 4) == 6!! This was due to our accidental swapping of index with value in our

reducer! Could we have made the same mistake with our triangulation approach? Yes we sure could have, but the point of

triangulation is to take the simplest scenario (i.e. the one you can deduce all inside your noggin) and expand upon

it over and over again until the correct approach falls out. Throughout this triangulation process, say when we add

in the test case for 1, 2, 3 we very well might need to completely re-write our implementation but do you know

what we don't need to re-write? All the tests we wrote up until the point.

Writing a single test, especially if you write it after the implementation is opening yourself up for failure. You need to write the absolute minimum amount of code to prove the simplest test case so that you can build yourself up to a point at which your complicated edge cases have simple scenarios backing them up and saving us from ourselves.

Taking Notes

Out of everything covered in this book I believe that this will result in the biggest change to my day-to-day coding. I find myself regularly storing way too many edge cases in my head with the plan to write that very test as soon as I complete the one I am working on now; but I inevitably get called aside and 100% forget to do so.

I have also on occasion wrote all 10 edge cases down as individual test without making my red tests go green, which inevitably leads to large amounts of code re-writing as I discover through my testing that I need to take another approach to running my tests.

Both of these failures can be avoided by treating your ideas the same way you treat your red to green step of testing, take the absolute simplest step to get from red (idea in my head) to green (idea guaranteed to be covered). The way this can be achieved is through a simple checklist via whatever tool you like to use to make notes (pen and paper very well might be the best approach). Instead of getting distracted and forgetting OR incorrectly following TDD just write it down and cross it off when you do it.

Simple.

Write tests that speak to you

I have talked mostly about the red and green steps of tdd but not much about the refactor step. Refactoring is typically something that a developer does to the codebase they are working on to reduce duplication and improve readability, but it's not only production code that can be refactored.

If you have an identical approach to how you do the //act phase of your unit tests that involves calling the function

with either a test parameter OR a default, then extract that logic into a function and just call the same act function

for each test scenario. Setting up a default piece of test data in each test? Why not extract it?

TDD and legacy Code

The book raised that quite often you are not in a situation in which you have a well tested codebase in front of you, sometimes you need to fix a bug a few hundred lines deep into a really horrific function. "Write the tests you wish you had." is a direct quote from the book and I couldn't agree any harder with that idea if I tried.

I would further add to this discussion the idea of isolating bad code as such as this with an integration test that combines all the dependencies from top to toe that are involved with this problematic code and then supply mocks for the outer edges which contain non-deterministic actions as such as reading or writing to an external source.

From there we can aim to add more and more coverage until we reach a place of confidence that allows us to refactor out duplications and re-arrange to our hearts content. As we continue this process over and over we will eventually reach a point in which we are able to have the problem parts of our codebase or the places that need new features fully isolated. It is from there that we can start to apply more rigorous unit testing as we apply fixes or add new functionality. During this time of code change all the tests that we wished we had will be covering for us and making sure we don't break things.

Assert first

this is a cool new pattern I found in the book, if your not sure how to write your test, start with assertions, move to executing (act) and finally the arrangement that normally is the first part that is written.

Leave your codebase Broken

Another cool trick raised by the book is when your finished for the day or need to pop out, leave a test broken as it gives you an instant reminder into what it was you were trying to achieve.

My overall thoughts on the book

I came into this book expecting to disagree with a lot of what it had to say as a practitioner of the London School of testing, however this book has helped me to realise that Detroit is the building blocks of TDD, with London being an expansion of tools and practices that enable you to further expand your code quality deeper into the architecture of your code solutions.

Assert first and note-taking were probably the most impactful lessons I have learnt and I will be trying to help my team realise these cool strategies. I would highly recommend this to anyone who has an interest in Testing and I would especially recommend it to anyone actively practicing TDD looking to find improvement.